A little less than two years ago, I wrote a guest blog post for the Oxford University Press about my first dissertation chapter. I just realized, however, that I did not end up writing follow up posts on my other dissertation chapters. Therefore, I decided, both as a way to get back into blogging and to continue the story of my dissertation, I will write a blog post for each of my other dissertation chapters, with another post or two on how the work has continued since my dissertation.

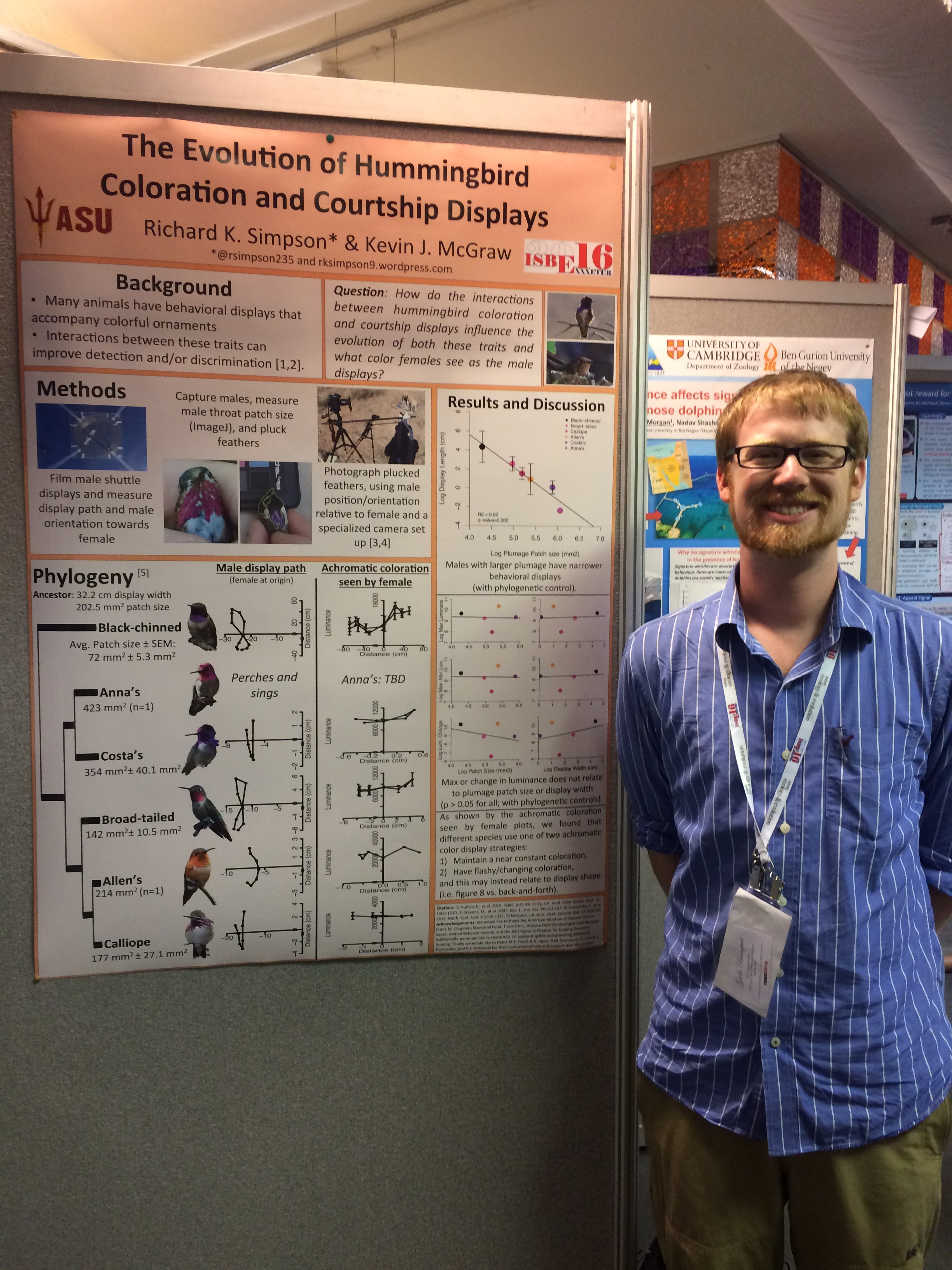

First, a brief reminder of where the story of my dissertation began. I was interested in understanding the diversity and evolution of hummingbird iridescent coloration and courtship dances. I was particularly excited to study how male hummingbirds used their dances and the environment to manipulate their angle-dependent iridescent coloration.

Throughout my work, I termed these color manipulation events as “signal interactions” because the behavioral signals, color signals, and the environment in which the signaling took place were all interacting with each other to produce how males appeared to females during courtship. I also used the term “male color appearance during displays” or “color appearance” for short to describe this signal interaction product. To provide a little more context and examples, though my first dissertation chapter, I found that some male hummingbirds use their behaviors and the environment to manipulate their iridescent feathers to create a flashy, strobe-like color appearance. Think of someone dancing in a sequin outfit – when they move about, their outfit will sparkle and flash, which is similar to what some hummingbirds do. Other hummingbirds maintain a very consistent color appearance during courtship. In other words, they behaviorally and environmentally manipulate their iridescent coloration to not change color as they dance.

In addition to finding this variation in male color appearance during displays, I also wanted to understand what exactly was driving that variation. One of the main findings from my first chapter was that how males oriented towards the sun greatly influenced their color appearance. Some males tended to face away from the sun as they courted females, and these males tended to have the consistent color appearances. Other males tended to face towards the sun as they courted females, and these males tended to have the flashy color appearances. There were also multiple aspects of each male’s display that influenced their color appearance, such as how they oriented towards the female as they danced. Also, all of the work for my first chapter was on broad-tailed hummingbirds.

So, the main findings from my first chapter were 1) male hummingbirds use courtship dances and the environment to manipulate their iridescent plumage to produce two types of color appearances for females – flashy color appearances and consistent color appearances; and 2) male hummingbirds vary in how they orient towards the sun as they dance for females, which in turn predicts their color appearance.

For my second chapter, which I published in Ecology Letters in 2018, I wanted to better understand how male iridescent plumage, courtship dances, and the environment were interacting to produce male color appearance. Did one or more of those traits play a stronger role in the production of color appearance? For example, did males with brighter and more colorful plumage appear brighter and more colorful? Or could males with any sort of plumage be able to achieve a variety of color appearances through their dances? These were the questions I aimed to study going into my second dissertation chapter. For this work, I shifted to a different hummingbird species, the Costa’s hummingbird.

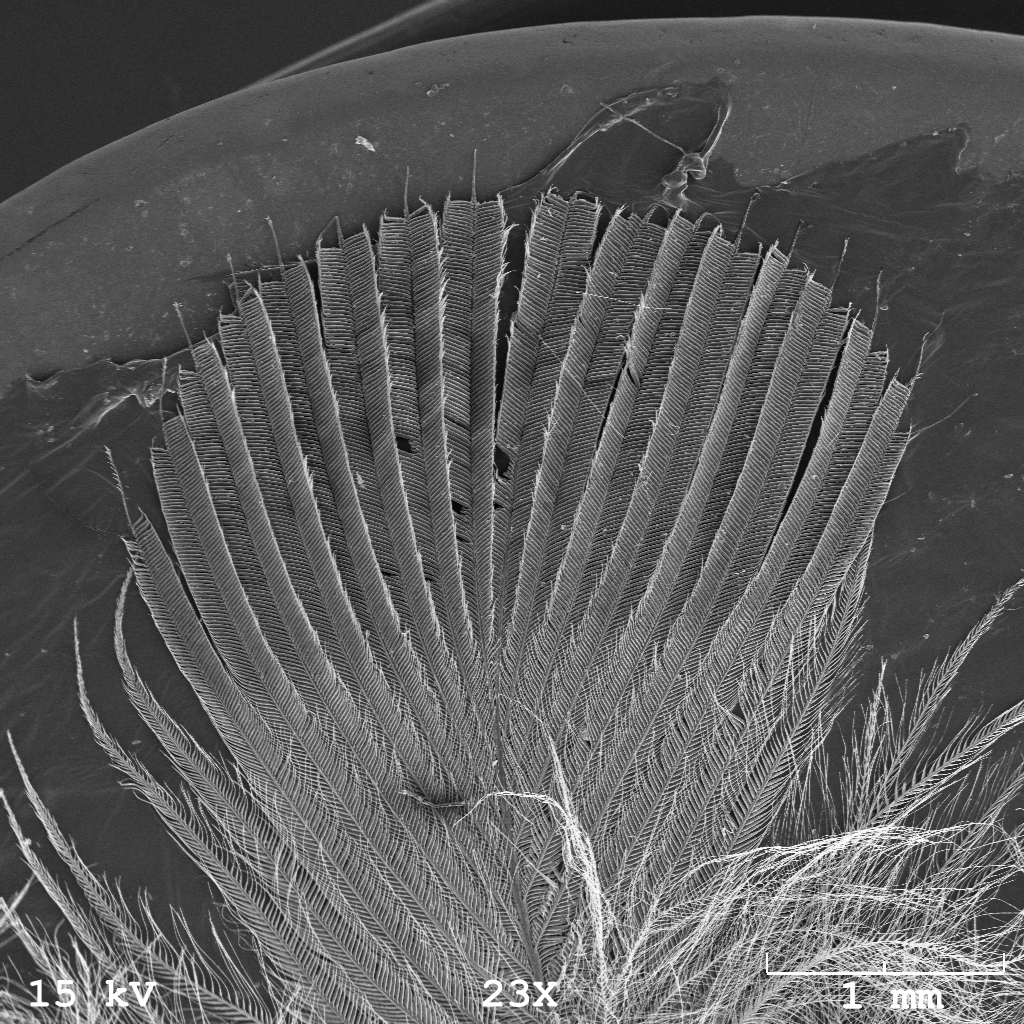

Costa’s hummingbirds are desert specialists, unlike the high elevation broad-tailed hummingbirds, and Costa’s hummingbirds are very abundant in southern California, where I studied them. I used the same field techniques as I did for my first chapter. I used caged females to elicit and film male courtship dances (second video). I captured those males who danced and collected a few feathers from them. I used video tracking software to map male movements and plumage orientations towards the sun and female during courtship dances. And finally, I used a tool I built, which I called the lazy Susan apparatus, to take male feathers and move them through a re-created male courtship dance and quantify the appearance of those feathers as they moved through the dance.

Altogether, I had data on male courtship dance behaviors, solar orientation, and color appearance, just as I did for my first chapter. However, in this chapter I made two major additions. Firstly, I had a much higher sample size, meaning I filmed more courtship dances from more males, which allowed me to do more complex statistical analyses. And secondly, I took those plucked feathers and also took objective color measurements of the feathers outside of their behavioral and environmental contexts. In other words, instead of only measuring color appearance during a display, I took standardized measurements of feather color. Namely, I measured feather reflectance using a spectrometer. This allowed me to test whether males with innately more colorful or brighter feathers appeared more colorful or brighter during their display. Also, because iridescent feathers change color depending on the angles in which they are illuminated or observed, I used the spectrometer to measure how angle-dependent each male’s feathers were. This allowed me to test whether males with more angle-dependent feathers appeared flashier during their displays.

Using all of these data, I created a series of statistical models that tested the predictive influence of male courtship dances, feather reflectance, and solar orientation on male color appearance – both in terms of flashiness and how bright and colorful males appeared on average. First, I should note that unlike male broad-tailed hummingbirds, which exhibited a large variation in how they oriented towards the sun, nearly all male Costa’s hummingbirds faced the sun as they displayed.

Okay, back to my models. I found that while all three signaling traits – feather reflectance, behavior, and the sun – predicted variation I male color appearance, but variation in male behavior and especially solar orientation were much stronger predictors of color appearance than feather reflectance. To me this was very exciting, because it meant that even the males who had drabber plumage to begin with were able to behaviorally and environmentally manipulate their iridescent coloration to appear bright, colorful, and flashy. This finding lead to my cheeky paper title – “It’s not just what you have, but how you use it.”

These results have large implications for understanding color signaling in general. Many researchers who study how animals use color as a signal, such as to attract males (like the hummingbirds) or to ward off predators or rivals, measure the color of a given animal outside of their behavioral and environmental contexts. In other words, they use a spectrometer, or something similar, to measure color reflectance, as I did in the lab. However, my results here demonstrate that knowing color reflectance does not tell the whole story. In fact, it might not even be telling any story, because of how animals, like my hummingbirds, can manipulate their color to change how it appears. My big hope for color signal research going forward is that researchers focus more on how animals are behaviorally using their colorful signals and how these signals are interacting with the environment, which I believe will go a long way into helping us understand why and how animals use color to communicate.

Here is the full citation for my second dissertation chapter, which again was published in Ecology Letters:

Simpson, RK, McGraw, KJ. 2018. It’s not just what you have, but how you use it: solar-positional and behavioural effects on hummingbird colour appearance during courtship. Ecology Letters, 21: 1413-1422. PDF

Next time, I will write about my third dissertation chapter, which builds upon my first two chapters by comparing male hummingbird signals and signal interactions across species. More soon!