This is actually a post I’ve been thinking about writing for a while now. But before I get started on giving my advice on writing grants, I want to give a little bit about my experience in grant writing, to give a little more substance and context to the advice. While I was in graduate school, I wrote a lot of grant applications, and by a lot I mean 71 different grants over those six years. Of those 71 grants, I had 42 of them successfully funded (59%), which totaled to over $100,000 USD. These grants ranged from small $500 grants to large, $20,000 multi-year project proposals, like the now defunct NSF DDIG (sadness). I also took a grant writing course during my first year of grad school and have received feedback on my grants from many different professors, post-docs, and grad-students. However, I will say that my grant writing experiences could still be very different from yours, especially if you are outside of the United States or in a very different field than me. So, disclaimer: these are my thoughts and opinions and they do not guarantee grant success, though these writing practices did work very well for me.

Now to get down to it. How does one write a successful grant? Well the first thing to do is carefully and thoroughly read the grant call or ad. This might sound obvious, but I have found many people do not do this, and often get their grant applications quickly rejected for various reasons related to this. Why is it so important to read the call? First of all, the grant call will describe what the grant is for – the specific scientific discipline or the type of work (for example – field work) – and who the grant will be reviewed by, which is of critical importance! If the grant is going to be reviewed by a general science audience (I am still assuming an academic audience here) then be sure to avoid discipline specific terms and narrow viewpoints. If the grant will be reviewed by specific sub-disciplines, for example if you are writing a taxa-specific grant, then make sure to mold your grant into something related to and important within that sub-topic or taxa. Also, some grants will request or require specific sections within your materials, such as a conservation impact statement or statement of ethical consideration, which you would do well to include if you want to be seriously considered. Finally, the grant call will often lay out the specifics of the budget or funding uses, which are also very important (see below).

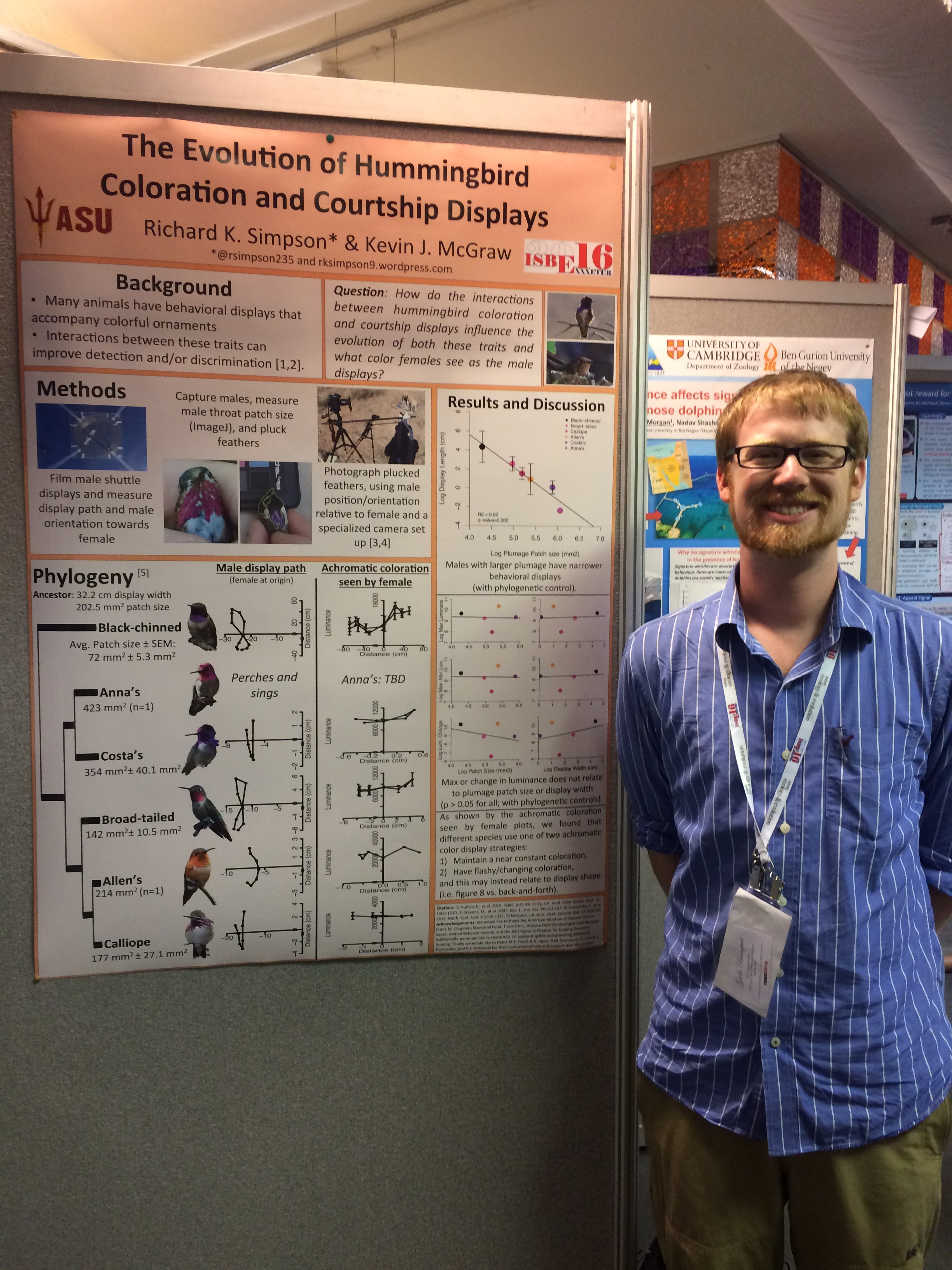

Next is actually writing the body of the grant – the introduction, purpose, proposed methods etc. I have sat on several different grant reviewing committees and have read a wide array of grants in terms of writing quality. One of the first things I notice is how well the grantee introduces their subject and why I (or the reviewer should care). A grant that starts out with something like “For this study, we will test how the iridescent feathers in black-chinned hummingbirds interact during male courtship displays which alters how those feathers appear to females to better understand how these traits evolved” is a terrible way to start a grant. There is no broader picture painted or lead up to the complex idea that is being tested and this is a very specific, out of context, research question that might interest one person out there, which is typically the person writing the grant. Instead, a grant on this topic should start out much broader, such as “Animals exhibit an incredible diversity of exaggerated traits that they use for communication, such as colorful peacock tails or the roars of lions, leading to the question of why this diversity evolved?” This introduction puts forth a much broader concept that is typically interesting to a wider audience: understanding the diversity of traits animal use to communicate. Additionally, it uses more widely known examples – pretty much everyone knows what a peacock looks like or what a lion sounds like, whereas fewer people might know the specific color patterns and courtship behaviors of a black-chinned hummingbird (though if you check out these videos you will now know!). My point in all of this is that you need to start broad with your grant introduction and then narrow down on your particular project. You have to hook the grant reviewer to get them interested, and then draw them in slowly to keep ahold of that interest. And you also must absolutely avoid jargon! None of this cell line XD72k or gene 338s7893. Those details often don’t matter, or if they are critical to the project, put them in the methods with a brief explanation.

After you have written the introduction or background to your grant, be sure to clearly state the purpose of your study. What is the specific question you are testing? What is your hypothesis? If you can fit in predictions, even better! I know some grants are very limited space-wise, but these are important parts of a grant so that you show that you not only understand the background and potential importance of your work, but that you have designed a clearly laid out study. In the end, the grant reviewers want to fund projects that they think will a) actually occur, and b) be successful. And by successful, I do not mean that you will get the exact results you want, but that the project will be completed and yield some sort of results that will hopefully be publishable.

This brings me to another point, which is more about project design in general, but still relevant here. Be sure that the study you have designed and are proposing in your grant is not answering an all-or-nothing type question. By this I mean, be sure that when you get your results, if they do not end up as you predicted, that they will still be interesting, and not mean nothing. There are too many studies out there, where if the exact results predicted are not obtained, then there is no alternative hypothesis or conclusion. That is just bad experimental design.

For the methods of the grant, be thorough but brief. You need to make it clear that you have a concrete plan and know what you are doing, but do you not have to write out every detail for your experiments (and you will often not have the space to do so). Use citations to help fill in extraneous details or shorten the methods section. And again, keep the text free of jargon, especially if this is a more general science grant. I’ve had to write grants/methods as a behavioral and evolutionary ecologist that a molecular biologist would have to understand, and you likely will too.

One of the last parts of a grant is often the proposed budget. This is another place where I have seen many mistakes in grants that ended up sinking the proposal completely. The first major piece of advice I have is do not propose a budget that is higher than what the grant can provide. The ONLY time you can do this, is if you have already obtained funding to match what will be required outside of the grant you are applying to AND you mention this in the budget. This is very important, because if the maximum grant award is $2000 for a specific grant, and you write a project with a budget for $5000 without evidence that you have the remanding funds, then you will not get funded, because if you receive the $2000 from this grant, but do not obtain the remaining $3000, then your project will fail. If your project does require a bigger budget than the grant you are writing for, then focus down what you ask for and/or request funds for specific components. For example, if you are requesting funds for fieldwork – shorten the length of the work to fit within the grant’s budget. Then apply for more grants and if you get them, you can go back to your originally planned field season length, but if you do not, you can at least work in the field for some time, which is better than none!

Another common mistake with budget writing comes from not reading the grant call specifics, as I mentioned above. Some grants, especially societal grants, will have restrictions on what they can fund. For example, many grants will specifically say that they will not fund hired help or field assistants. Well, if you request money for a field assistant, then you will not get that grant. Only ask for what the grant allows you to ask for.

To avoid having an overly long post, the last thing I will suggest here is get someone, especially your advisor if you can, to read your grant and give you feedback. At the very least they can help catch poor grammar, confusing wording, or spelling errors, which can easily sink a grant as well. I have often received incredibly helpful advice on the phrasing of certain parts of my grants, which ultimately made it into the papers produced from the funded work, which leads me to another point. If you write a good grant introduction and methods section, you can easily expand them into a future paper, saving you both time and energy in the long run. I have done this with several of my dissertation chapters myself.

I hope this advice will be helpful for when you write your next grant, and please let me know if they are or if you have any further suggestions! If there is enough interest, I may write a second post on this topic as well. Best of luck to you all with your grant writing!